Today we honour the extraordinary sacrifice of those members of our own community who died so that we might live in freedom. Whilst military historians endeavour to record battlefield losses with a keen eye for numerical accuracy, grief will always constitute a profoundly human experience, for there is no expiration date on the dreadful sense of loss and emptiness that arises from the sudden absence of those whom we love.

Each name carved into the beautiful Collingwood Cross that stands outside the Chapel records the devastating loss of a life cut short by the maelstrom of war. Almost a hundred and seven years after the signing of the Armistice, we reflect upon the deaths of those of our community whom we should count as our own. It was often said that a whole generation of young men was lost during the First World War. From a national perspective this was a slightly hyperbolic statement, but here at Bradfield it must have felt as if a golden generation of young men had been swept away. So much potential and so much promise was lost in the mud, trenches and slaughter of the Western Front.

Two hundred and seventy-nine Bradfieldians are known to have died during the First World War and a further hundred and ninety-eight Bradfieldians died during the Second World War. Two Bradfieldians have died in subsequent conflicts. When the Collingwood Cross was erected in 1916 it bore the names of one hundred and fifty-nine Bradfieldians. By the time the war had concluded, another a hundred and twenty names had been added to it. In 1951, the monument had to be moved to its current position, in order to accommodate the names of those who lost their lives during the Second World War.

In recent weeks, I have been reflecting a good deal upon the lives of individual Bradfieldians who served during the First World War. I was particularly struck by the story of Francis John Maclardie Chubb who died at the age of twenty-one on 18th April 1915 whilst attempting to capture Hill 60 which was an important strategic point on the Ypres salient. Francis’ father Edward died fighting on the Western Front in early July of the same year. That a wife and mother should lose both her son and her husband just weeks apart seems unspeakably cruel.

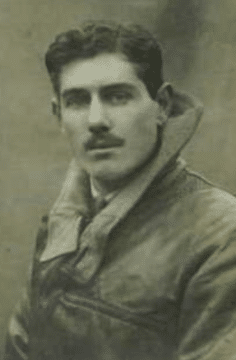

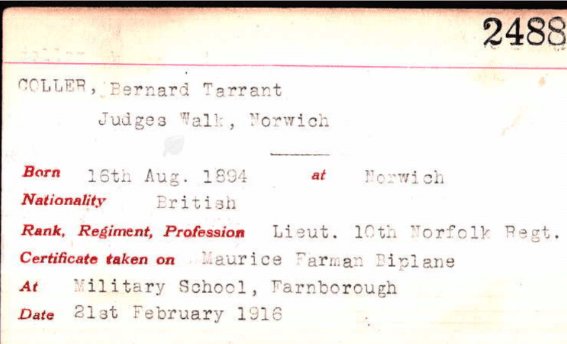

Bernard Tarrant Coller was born on 16th August 1894 to a family who lived in an affluent part of Norwich. His father, Charles was a successful coal merchant and a landowner of some standing who employed over a hundred men. His mother Maud was some six years younger than Charles and came from Surrey. Little is known of her background. The couple married two months after the birth of Bernard and went on to have four more children. Their two sons, Charles and Raymond, were followed by two daughters, Patience and Audrey.

Bernard was sent to a preparatory school in Eastbourne before progressing to Bradfield College in 1908. During the following years, The Bradfieldian Chronicle records Bernard’s impressive sporting prowess. He excelled in the senior steeplechase and played cricket with some distinction. From an early age, Bernard clearly possessed a practical disposition and an interest in mechanics. We are told that he helped operate the ‘machinery’ in the Greek play and displayed a keen interest in tinkering with other people’s motorbikes. He was a school prefect and went up to Oxford in the summer of 1913 where it is reported that he was on course to achieve a half blue in golf. He returned to play for the Old Bradfieldians in the summer of 1914 just weeks before war was declared.

At the outbreak of the war, he put his studies on hold and joined up. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant into the 10th Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment. The 10th Battalion was a reserve battalion, and Bernard may well have become frustrated by the fact that he had not seen active service. Consequently, in late 1915, he joined the military school at Farnborough and trained to fly on a Maurice Farman Biplane. These flimsy planes were designed for reconnaissance purposes and although they were considered relatively easy to handle, they had an uncanny habit of suddenly stalling and nose-diving with catastrophic consequences. Nevertheless, Bernard passed his training on 21st February 1916.

Bernard joined the 9th Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps and was involved in early contact patrol missions over enemy territory. Before long, Bernard was flying alongside the accomplished observer, Second Lieutenant Thomas Scaife. It should be remembered that the life expectancy of Royal Flying Corps pilots was often to be measured in weeks. Some referred to these pilots as belonging to the ‘Twenty Minute Club’ because so many of them would die during the first hours of combat. Bernard fared slightly better but, alongside Thomas Scaife, he was shot down and killed on 26th September – just seven months after completing his initial training in England. His body was never recovered, and his name is recorded on the Arras Flying Services Memorial which commemorates the names of almost a thousand young British airmen who have no known grave. Bernard was just twenty-two years old.

Bernard’s family must have been utterly devastated by his sudden death but worse was to follow. Bernard’s younger brother, Charles, who had attended Charterhouse before the war, joined the 4th Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment in October 1914. He rose to obtain the rank of captain but was killed on 21st March 1918 whilst fighting very close to where his brother had been killed a little more than eighteen months earlier. Like Bernard, he had no known grave, and he is remembered on a memorial in the same cemetery as his brother. This memorial contains the names of over thirty-five thousand servicemen who fell in this small area but have no known grave. Like his brother, he was just twenty-two years old when he died.

Of the three Coller brothers, that just left Raymond, He had attended Rugby School before joining the 17th Battery of the Royal Field Artillery towards the end of the war. Raymond headed to the Western Front in July 1918 and briefly saw active service but, mercifully, he survived. After the end of the war, he went up to Oriel College in Oxford before settling back down in his home city of Norwich and becoming a director at the well-established brewery of Youngs, Crawshay and Youngs. Raymond also joined the Territorial Army and obtained the rank of major before retiring from the forces in 1928. Raymond married and had four children with his wife Beryl.

After a conflict that had taken both of his brothers, he surely deserved to live out the rest of his years peacefully in Norfolk. However, this was not to be, because soon after the outbreak of the Second World War, Raymond was recalled to the army. He soon found himself stationed in Watford and he was accompanied by his wife Beryl and his youngest two daughters, Sonia and Jane, who lodged at the Rose and Crown Hotel nearby. When the hotel took a direct hit, it was decided that Beryl and the youngest two children should relocate back to the relative safety of Norwich. Raymond accompanied his family back to Norwich during a period of leave.

Returning to his duties with his regiment, Raymond caught a train to London where he was due to change for the connection to Watford. The train took a direct hit and Raymond was badly injured. He was thrown on to the line and, consequently, lay undiscovered for several hours. He was later taken to hospital, but his wounds became infected, and he died of blood poisoning just three days later at the age of forty-one. He left behind his wife and four young children.

By contrast, the mother of Bernard, Charles and Raymond lived a very long life indeed. She was born in 1866 and lived well into her nineties. It is impossible to imagine how she kept going given that she had lost all three of her sons during the First and Second World Wars. The dreadful toll that the major conflicts of the twentieth century took upon the Coller family might seem a little remote to yhose of us sitting here in 2025, but Audrey, the youngest sister of the three brothers lived on until 2008. To put that in context, if you are in the Upper Sixth Form then your life will have briefly overlapped with the life of someone who was very much at the centre of the tragic events I have just described.

As of 2024, the Global Peace Index assesses that ninety-two countries are actively involved in conflicts. Whilst George Santayana warned that those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat history, the German philosopher Hegel bleakly concluded that all we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history. In a world beset by tension and conflict, we bring close to our hearts all those who are currently suffering because of humankind’s seeming inability to live alongside one another in peace. We think especially of those in the Middle East and Ukraine, and we pray for a time when, as it states in the Book of Isaiah,

They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore

As we remember the sacrifice of Bradfieldians like Bernard Tarrant Coller, we do so with grateful hearts and with the individual and collective resolve to honour their memory by living good and purposeful lives. For all eternity, Bradfieldians should remember the names of the fallen with absolute pride.